RAF Metheringham

RAF Metheringham, Tiger Force and the end of WW2

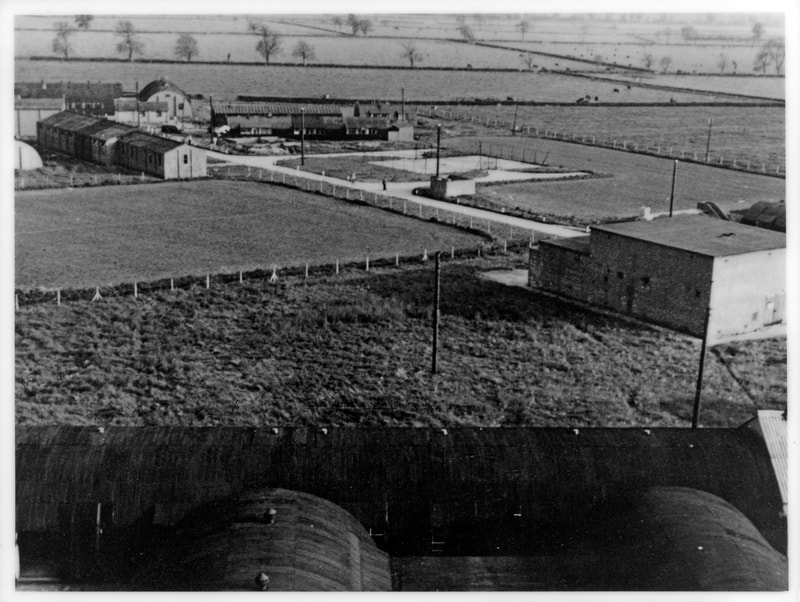

In the Summer of 1945, with the war in Europe now over, Allied attention turned exclusively to concluding the war against Japan. The RAF planned to bolster air power in the Pacific theater with the formation of "Tiger Force" - Squadrons of long range Lancasters and Lincolns that were to be based in the region to support the proposed invasion of Japan by Allied forces. However, following the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August 1945, Emperor Hirohito of Japan surrendered to the Allies on the 15th August. This brought an end to World War 2 and at the same time removed the requirement for the formation and training of the Tiger Force. RAF Metheringham was to be instrumental in the short life of Tiger Force as 106 and 467 squadrons, both Tiger Force squadrons, were based there. To accommodate the latest heavy bombers, there were plans to extend the main runway to 10,000 ft and the secondaries to 6000 but they were immediately shelved, and 467 Squadron was disbanded thus accelerating the demise of the airfield.

Source: Andy Marson (FOMA)

In the Summer of 1945, with the war in Europe now over, Allied attention turned exclusively to concluding the war against Japan. The RAF planned to bolster air power in the Pacific theater with the formation of "Tiger Force" - Squadrons of long range Lancasters and Lincolns that were to be based in the region to support the proposed invasion of Japan by Allied forces. However, following the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August 1945, Emperor Hirohito of Japan surrendered to the Allies on the 15th August. This brought an end to World War 2 and at the same time removed the requirement for the formation and training of the Tiger Force. RAF Metheringham was to be instrumental in the short life of Tiger Force as 106 and 467 squadrons, both Tiger Force squadrons, were based there. To accommodate the latest heavy bombers, there were plans to extend the main runway to 10,000 ft and the secondaries to 6000 but they were immediately shelved, and 467 Squadron was disbanded thus accelerating the demise of the airfield.

Source: Andy Marson (FOMA)

Tiger Force

At the Quebec Conference of September 1944, Churchill told Roosevelt that once the war in Europe was over, Britain would provide a Very Long-Range Bomber Force to support the Americans in the fight against the Japanese. At that time, it was estimated that it would take a further 18 months to defeat the Japanese once the war in Europe was over. Air Marshal Sir Hugh Pughe Lloyd was designated commander of what was called Tiger Force, which would comprise primarily the RCAF No 6 Group and No 5 Group. Initially, the RAF was told it would have to build their own airfields.

After VE Day, the Canadians returned to Canada to work up for Tiger Force in Canada. Within 5 Group there was a major re-organisation in the work up for Tiger Force. 467 moved to Metheringham and 463 moved to Skellingthorpe, whilst 460 Squadron moved from Binbrook in 1 Group and joined 57 Squadron at East Kirkby. 9 & 617 Sqn moved into Waddington and were designated as the Special Weapons Wing, with their Tallboy bombs. Some of the targets in Japan had been identified as Tallboy targets. For the Australian squadrons it was important to them to be part of Tiger Force as back in Australia the Australian squadrons in the UK had been accused of being 'Jap Dodgers'. 106 and 467 Squadron formed 552 Wing of Tiger Force whilst 57 & 460 Squadron were part of 553 Wing. In a talk by Bill Taylor some time ago, he highlighted that the ship carrying advance party of 9 & 617 Squadron personnel also had Tallboy bombs on board. Bill had been unable to find out what happened to these bombs. Were they dropped overboard?

The F540 records show that Metheringham was a one squadron austere wartime airfield and suddenly it was home to a second squadron, and one got the impression there was a certain friction between the two squadrons. For example, there now had to be two showings in the cinema. Reading the entry for the surrender of Japan was also interesting. I quite liked the sentence that said that "the flares in the watch tower had been made safe". I got the impression that someone had wanted to set the flares off in celebration! The next two days were put over to 'working parties' - my interpretation was that there was a lot of clearing up to do after the party! 467 Squadron disbanded at Metheringham on 30th September 1945. The entry in the 467 Squadron F540 mentions that the AOC of 5 Group was at the disbandment parade and thanked the Australians for their efforts. Contrast this with the Metheringham F540 which just said that the AOC visited Metheringham. With the demise of Tiger Force, 5 Group was disbanded.

Source: Phil Bonner (Historian).

http://www.lancaster-archive.com/lanc_tigerforce.htm gives the following extra information. The force was to be based in Okinawa and three squadrons due to be operational by January 1946 were based at RAF Metheringham, 106 Squadron and 467 Squadron using Lancasters and 544 Squadron Mosquitos.

At the Quebec Conference of September 1944, Churchill told Roosevelt that once the war in Europe was over, Britain would provide a Very Long-Range Bomber Force to support the Americans in the fight against the Japanese. At that time, it was estimated that it would take a further 18 months to defeat the Japanese once the war in Europe was over. Air Marshal Sir Hugh Pughe Lloyd was designated commander of what was called Tiger Force, which would comprise primarily the RCAF No 6 Group and No 5 Group. Initially, the RAF was told it would have to build their own airfields.

After VE Day, the Canadians returned to Canada to work up for Tiger Force in Canada. Within 5 Group there was a major re-organisation in the work up for Tiger Force. 467 moved to Metheringham and 463 moved to Skellingthorpe, whilst 460 Squadron moved from Binbrook in 1 Group and joined 57 Squadron at East Kirkby. 9 & 617 Sqn moved into Waddington and were designated as the Special Weapons Wing, with their Tallboy bombs. Some of the targets in Japan had been identified as Tallboy targets. For the Australian squadrons it was important to them to be part of Tiger Force as back in Australia the Australian squadrons in the UK had been accused of being 'Jap Dodgers'. 106 and 467 Squadron formed 552 Wing of Tiger Force whilst 57 & 460 Squadron were part of 553 Wing. In a talk by Bill Taylor some time ago, he highlighted that the ship carrying advance party of 9 & 617 Squadron personnel also had Tallboy bombs on board. Bill had been unable to find out what happened to these bombs. Were they dropped overboard?

The F540 records show that Metheringham was a one squadron austere wartime airfield and suddenly it was home to a second squadron, and one got the impression there was a certain friction between the two squadrons. For example, there now had to be two showings in the cinema. Reading the entry for the surrender of Japan was also interesting. I quite liked the sentence that said that "the flares in the watch tower had been made safe". I got the impression that someone had wanted to set the flares off in celebration! The next two days were put over to 'working parties' - my interpretation was that there was a lot of clearing up to do after the party! 467 Squadron disbanded at Metheringham on 30th September 1945. The entry in the 467 Squadron F540 mentions that the AOC of 5 Group was at the disbandment parade and thanked the Australians for their efforts. Contrast this with the Metheringham F540 which just said that the AOC visited Metheringham. With the demise of Tiger Force, 5 Group was disbanded.

Source: Phil Bonner (Historian).

http://www.lancaster-archive.com/lanc_tigerforce.htm gives the following extra information. The force was to be based in Okinawa and three squadrons due to be operational by January 1946 were based at RAF Metheringham, 106 Squadron and 467 Squadron using Lancasters and 544 Squadron Mosquitos.

The Java Jive

|

The Java Jive by the Ink Spots was the 106 Squadron unofficial ‘tune’ and Jeff Williams (FOMA Trustee) recalls that ‘some years ago I came across a World War 2 veteran, E Bilby who told me a story about a Lancaster crew who made a point of dancing to the Java Jive before each mission. Like all crews they were very superstitious. They knew that, however skilled and experienced you were, whether you got back alive was as much due to luck as anything else.

|

On one occasion they were in the MT on the way to board their aircraft when they realised that, for whatever reason, they hadn’t done their dance so they made the driver take them back to the mess so they could put the record on and complete their routine. She waited while they danced and then took them back to the dispersal. Click below to hear the 1940 recording they would have been listening to.

WAAF Memories at RAF Metheringham

Jean Danford of the MT section who drove the crew bus at RAF Metheringham, was, according to the recollections in the book "In The Middle of Nowhere" by Richard Bailey, integral to several other "excursions" where transport was required! Thank you to Tony Bazett (Curatorial Volunteer) for this snippet. You can read more about Jean in the book, "The Middle of Nowhere" by buying a copy from our shop on site.

467 Squadron Memories

|

A chance meeting at a Trustees Conference with our Curator, Caterina, led Robin Burrows to share his recollections of his father Leslie Burrows. He had served with 467 Squadron and was training for the Tiger Force when the war came to an end.

On the left image you see Robin (left) standing with Roger our very own Research Lead and Trustee, both next to our Dakota during Robin’s visit in 2019. The wartime image (right) is of his dad, seated, with his crew, location unknown. |

F/O John Daniel Trowbridge RAAF 467 Squadron

|

In March 1942 John Daniel Trowbridge an 18-year-old farmer from Lameroo in South Australia, enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force. He underwent training as a Wireless Operator/Air gunner and after qualifying in May 1943 he was posted to the UK. On arrival in England John had further training and along with his now crew was posted in June 1944 to 466 squadron RAAF at Driffield in Yorkshire. The crew was, except for the Flight Engineer, all Australian and they completed 37 operations either with 466 or 462 squadron RAAF flying Handley Page Halifax. Following VE day on 8th May, John like many Australians volunteered to join Tiger Force, in order to take the fight to the Japanese in the Pacific. He was posted to 467 Squadron then stationed at RAF Metheringham, and continued with training in readiness.

It was while he was at RAF Metheringham that John went to a dance in the village of Martin and met Eileen Flintham. She was a Metheringham girl serving in the Observer Corp. it was her uncle’s (George Flintham) land that much of the airfield was built on. After VJ day in August 1945, John was repatriated back to Australia in September. The following year 1946, Eileen sailed to Australia and married John. They settled on the family farm and raised three daughters. Sometime later Eileen's parents Violet and Jim Flintham also joined them on the farm in South Australia. John passed away on 22nd January 1998 aged 74 and he never spoke about his war time experiences. Eileen died 16th August 2015 aged 91 and they are buried in the War Graves at Centennial Park, Adelaide. Source: Roger Brindley (MAVC Research Lead) |

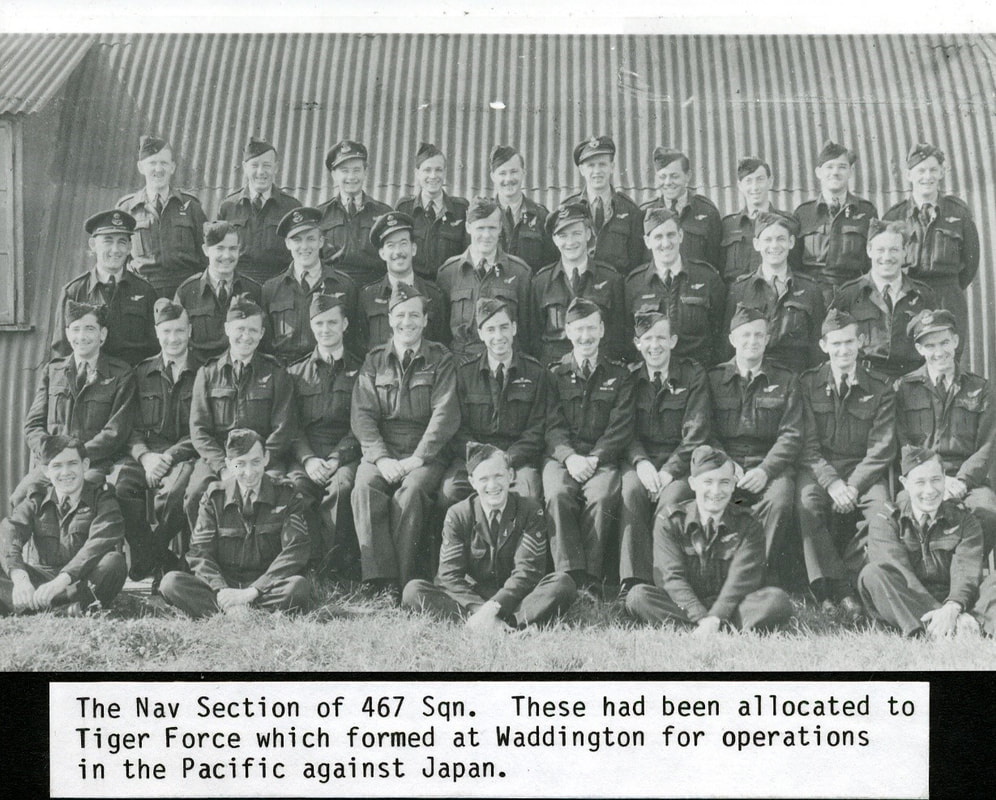

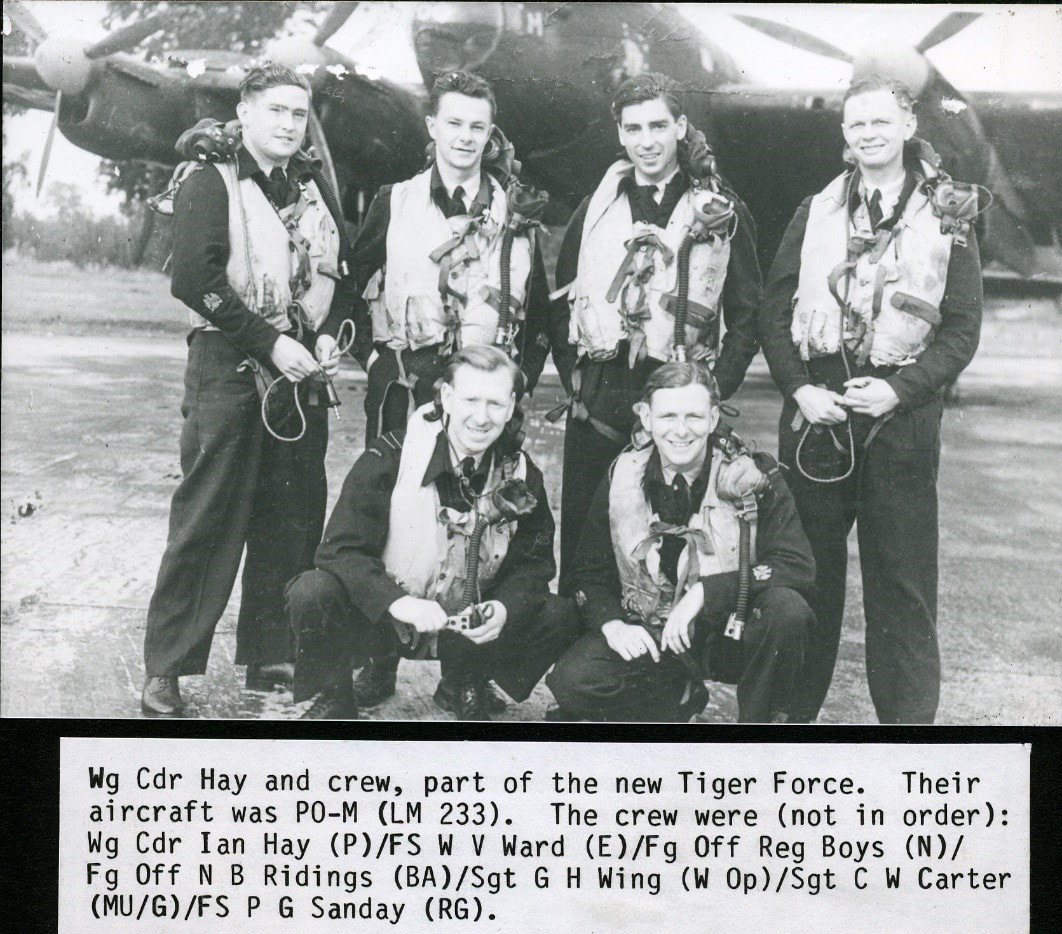

467 Squadron at RAF Metheringham

|

These photographs have been kindly included by permission of RAF Waddington Heritage Centre. The 467 Sqn Navigator section post war photo (left) is probably taken at RAF Metheringham and not RAF Waddington. Also, the crew photograph (right) of Wg Cdr Hay (OC 467) during the Tiger Force period.

If you recognise anyone in these photographs or know more about them that you would like to share, we would like to hear from you. |

Lancaster PB304 (ZN-S) - Salford Crash - 30th July 1944

Early on the morning of the 30th July 1944, 21 aircraft took off from RAF Metheringham to join a force of 185 Lancaster's for an attack on Cahagnes in the Normandy battlefield area in support of ground forces. The weather was cloudy and raining when take off started at 05:50. At the target area poor visibility and cloud cover prevented the target being identified. The Master bombers at several aiming points decided to abandon the operation and ordered all aircraft to return to base. It was now prohibited to jettison bombs as had been the standard practice for fear of hitting friendly forces and so the aircraft had to return fully loaded. Weather conditions at Metheringham were improving and at the briefing before take off the crews were informed that the return route was to be a long diversion to allow time for further improvement before landing.

Lancaster PB304 ZN-S captained by F/L P Lines took off at 05:55. F/L Peter Lines was an experienced pilot, although he was relatively new to 106 Squadron, his first operational flight was on the night of the 7/8th July. What happened to his aircraft we do not know. Whether it was damaged by enemy fire over the target or if there was a mechanical problem on the return journey, as he was passing over Greater Manchester it lost height. As the aircraft passed over Pendlebury, Salford eye witnesses claimed that the aircraft had a problem with a Port engine. The aircraft approached from the West appearing to be aiming for Littleton Road playing fields next to the River Irwell. F/L Lines may have been guided by his Flight Engineer Sgt. Raymond Barnes who was local to the area; he lived a mile away. F/L Lines made an attempt to land passing low over Langley Road and down Regatta Street but pulled up and went round to try again. On the second attempt to land a wing tip struck the roofs of several buildings in Regatta Street and he lost control. The aircraft crashed into the far bank of the River Irwell. Witnesses said that for a minute nothing happened, it then exploded detonating the load of 18x 500lb bombs still on board.

The explosion killed all seven crew on board and two civilians on the ground, more than eighty people were injured and many buildings damaged or destroyed. The civilians who were killed were 45 year old Mr George Morris and 72 year old Mrs Lucy Bamford, both died as a result of their injuries.

The crew of PB304 were:

Flight Lieutenant Peter Lines - Pilot

Sergeant Raymond Barnes - Flight Engineer

Flying Officer Harry Reid - Navigator RCAF

Flying Officer John Steele - Bomb Aimer

Sergeant Arthur Young - Wireless Operator

Sergeant John Davenport - Mid Upper Gunner

Sergeant Mohand Singh - Rear Gunner

A memorial was erected to the crew of PB304 in Agecroft Cemetery, Langley Road. The stone was donated by a quarry owner from Halifax.

The following crew members were identified and their remains interned privately:

Flying Officer Harry Reid RCAF Kirkwall (St Olafs) Cemetery

Sergeant J B T Davenport Sedgley Churchyard, Sedgley, Staffordshire

Sergeant M Singh Golders Green Crematorium, London

The remaining crew members are listed as missing and remembered on the Runnymede Memorial, Surrey.

Lancaster PB304 ZN-S captained by F/L P Lines took off at 05:55. F/L Peter Lines was an experienced pilot, although he was relatively new to 106 Squadron, his first operational flight was on the night of the 7/8th July. What happened to his aircraft we do not know. Whether it was damaged by enemy fire over the target or if there was a mechanical problem on the return journey, as he was passing over Greater Manchester it lost height. As the aircraft passed over Pendlebury, Salford eye witnesses claimed that the aircraft had a problem with a Port engine. The aircraft approached from the West appearing to be aiming for Littleton Road playing fields next to the River Irwell. F/L Lines may have been guided by his Flight Engineer Sgt. Raymond Barnes who was local to the area; he lived a mile away. F/L Lines made an attempt to land passing low over Langley Road and down Regatta Street but pulled up and went round to try again. On the second attempt to land a wing tip struck the roofs of several buildings in Regatta Street and he lost control. The aircraft crashed into the far bank of the River Irwell. Witnesses said that for a minute nothing happened, it then exploded detonating the load of 18x 500lb bombs still on board.

The explosion killed all seven crew on board and two civilians on the ground, more than eighty people were injured and many buildings damaged or destroyed. The civilians who were killed were 45 year old Mr George Morris and 72 year old Mrs Lucy Bamford, both died as a result of their injuries.

The crew of PB304 were:

Flight Lieutenant Peter Lines - Pilot

Sergeant Raymond Barnes - Flight Engineer

Flying Officer Harry Reid - Navigator RCAF

Flying Officer John Steele - Bomb Aimer

Sergeant Arthur Young - Wireless Operator

Sergeant John Davenport - Mid Upper Gunner

Sergeant Mohand Singh - Rear Gunner

A memorial was erected to the crew of PB304 in Agecroft Cemetery, Langley Road. The stone was donated by a quarry owner from Halifax.

The following crew members were identified and their remains interned privately:

Flying Officer Harry Reid RCAF Kirkwall (St Olafs) Cemetery

Sergeant J B T Davenport Sedgley Churchyard, Sedgley, Staffordshire

Sergeant M Singh Golders Green Crematorium, London

The remaining crew members are listed as missing and remembered on the Runnymede Memorial, Surrey.

RAF Metheringham,

VE Day Memories - 8th May 1945

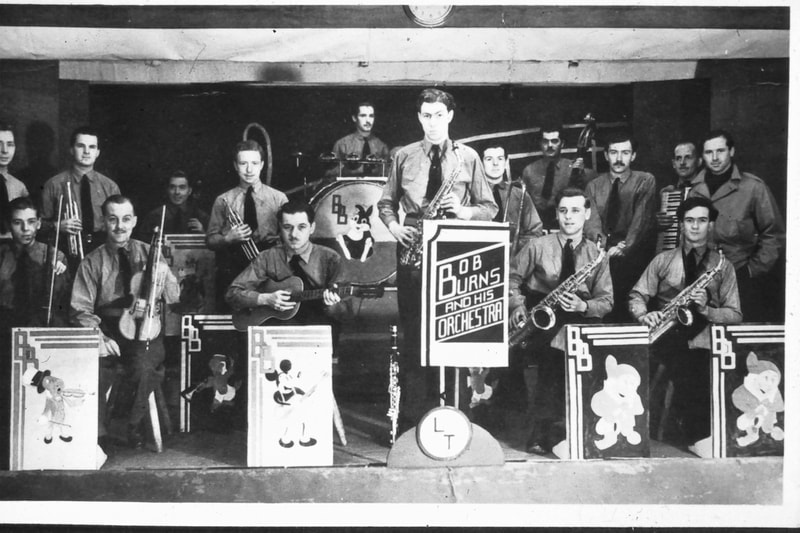

On VE Day, personnel at RAF Metheringham were stood down from operations and prepared to celebrate Victory in Europe with a huge dinner dance. The Repair and Inspection hangar was hastily turned in to a dance hall to accommodate the evening's entertainment and strips of "Window" (foil strips normally dropped from aircraft to confuse enemy radar) were suspended from the hangar roof as decorations. The station band assembled to provide a musical accompaniment to the evening's proceedings and locals from the surrounding villages were invited on to base to participate in the celebrations. Each mess provided a well stocked bar (local breweries had been asked to provide extra ale!) along with food that had been prepared in the messes during the day. Even as the station danced the night away, some crews were informed that they would be flying the next day. Several 106 Squadron crews took part in "Operation Exodus" flights to repatriate Prisoners of War back to the UK including flights on VE Day itself. Celebrations continued for several days, some formal, others less so. Personnel from RAF Metheringham were among many that attended a parade in Lincoln city centre to mark the end of the war in Europe. Up and down the country, people celebrated together with a mix of relief and happiness tinged with sadness as they remembered those that would not be coming home. Scroll down for more VE Day memories.

VE Day 75th Anniversary - Memories

Tony, our digitization volunteer, has fond memories of his father, Stanley Eric Curtis, who would have been 100 last year. He transferred from the Territorial Army to join the regulars on 3rd September 1939. He served in the Royal Artillery but spent a lot of his time attached to other units. Tony remembers him saying that he was really chuffed when he heard about the VE Day celebrations. Unfortunately, he could not join in as he was still up to his neck in muck and bullets in the Far East. He returned home from Burma via India in 1946. (Thank you Tony for sharing your memory.)

Marjory, a 91 years young member of FOMA, remembers VE day so clearly. She was 15 years old and had heard Churchill on the wireless the night before announcing that the next day, May 8th was going to be the end of the war. She was so excited and could not stay home. So on her own, she cycled a mile and a half to the nearest bus stop, the buses were running as normal, and went into the town of Wolverhampton. It was busy with all sorts of people, some from the local RAF stations and factories such as Bolton and Paul.

As she arrived in Queens Square, right in the middle of Wolverhampton, the place was heaving with people. There were so many nationalities, Polish, Dutch and service men home on leave. She remembers the Lyons Corner House waitresses dancing and not caring if their customers were being served, there were so many people all gathered in Queens square and dancing. Someone was playing the accordion and the atmosphere was electric. Then suddenly a young man started climbing up The Midland Bank building and people cheered him as he climbed up to the top and waved a handkerchief. Some people were sitting on top of the large horse statue of the Prince Consort, cheering and singing (see image). Marjory said she will never forget that day and it is a memory that is so vivid because everyone was so excited that it was the end of the war.

Marjory, a 91 years young member of FOMA, remembers VE day so clearly. She was 15 years old and had heard Churchill on the wireless the night before announcing that the next day, May 8th was going to be the end of the war. She was so excited and could not stay home. So on her own, she cycled a mile and a half to the nearest bus stop, the buses were running as normal, and went into the town of Wolverhampton. It was busy with all sorts of people, some from the local RAF stations and factories such as Bolton and Paul.

As she arrived in Queens Square, right in the middle of Wolverhampton, the place was heaving with people. There were so many nationalities, Polish, Dutch and service men home on leave. She remembers the Lyons Corner House waitresses dancing and not caring if their customers were being served, there were so many people all gathered in Queens square and dancing. Someone was playing the accordion and the atmosphere was electric. Then suddenly a young man started climbing up The Midland Bank building and people cheered him as he climbed up to the top and waved a handkerchief. Some people were sitting on top of the large horse statue of the Prince Consort, cheering and singing (see image). Marjory said she will never forget that day and it is a memory that is so vivid because everyone was so excited that it was the end of the war.

A little while after that day, as she was going to and from Wolverhampton Art College on the bus, she remembers there being big banners hanging from the windows of people’s homes saying ‘Welcome home (insert name) after five years away’, these were very common. Rationing went on for many years and in the spirit of these banners she remembers looking out of the bus window one day and saw one of these signs but it read ‘Welcome home Maggie after five hours in the fish queue’ what a fantastic sense of humour. Thank you Marjory for sharing your wonderful memories.

Christine, One of our Trustees, shared some memories that her husband David has of VE Day. Having just celebrated his 7th birthday on May 6th he was very excited that there was something else quite momentous to celebrate. He set about placing flags and bunting around the outside of his home at Parson Drove near Wisbech. Sadly his mother insisted that they were taken down immediately. Their neighbour had died and his mother felt it lacking in respect to show that they were celebrating. David was not happy! We still have some of the original flags!

Yvonne, aged 9 was based in Fairford, Gloucestershire where her father was a Warrant Officer in the RAF. This is her recollection of VE Day. “We were there for about 2 years. I used to like moving about when dad used to come home and say he was being posted, I loved it. I can remember the noise, the laughter and happiness. On VE Day, I remember the Americans singing and going and having a good time because we had won the war you see. They all did the Jive, it was an American dance. Everybody was happy, you know, we had won the war.”

Raymond was 13 and lived at Metheringham Fen, Lincolnshire, close to RAF Metheringham. This is his recollection of VE Day. “I lived down the Fen but I went into the village (Metheringham) with all my friends. They had a fancy-dress parade in the village and dancing and singing around the Star and Garter Pub and the village cross. Then there was a party with lots of food at Blankney Hall from the afternoon well into the night.”

Wartime Memories

Listen to the memories of Marjory Rea and Eric South about RAF Metheringham and wartime Lincolnshire.

Listen to the memories of Marjory Rea and Eric South about RAF Metheringham and wartime Lincolnshire.

Wartime Memories

Listen to the story of Ted Lucraft, an Armourer with 106 Squadron at RAF Metheringham

Listen to the story of Ted Lucraft, an Armourer with 106 Squadron at RAF Metheringham

Nuremberg Raid - 30/31st March 1944

If Berlin was the heart of the Nazi government, then Nuremberg was the spiritual heart. Hitler had held some of his biggest rallies in the city . Tens of thousands of German citizens came to pay homage to the Fuhrer in the city in the 1930s at mass rallies held at the Reich Party Congress Grounds south of the city.

Nuremberg is located in southern Germany in the federal state of Bavaria and is the second largest city after the state capital Munich. At the time Nuremberg was a centre of communications, industry and an administrative centre for the region and this made it a valid target for Bomber Command from early in the war. Bomber Command had visited Nuremberg on previous occasions starting in August 1940. In December an attack was made on the Nazi party rally grounds, rather symbolic. Air raids continued throughout the following years growing in size as Bomber Command and the USAAF ability to hit back grew. The heaviest raid up until then was on the night of the 10th/ 11th August 1943 when a force of 653 heavy bombers destroyed or damaged over 5000 buildings and killed 585 residents.

At the end of March 1944 Bomber Commands six month winter offensive was coming to an end . Often referred to as the Battle of Berlin it had cost Bomber Command heavily in casualties and lost aircraft but had not achieved its aim in bringing the war to an end by destroying the morale of the German people. Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris had promised that by April the German people would give up the struggle, however they seem to have adopted much the same “Blitz Spirit” as the British population had and carried on.

With the end of the period of long dark nights deep penetration raids into Germany would have to stop. Also with the prospect of the invasion of Europe, Bomber Command would need to change the type of target it selected, indeed the choice would be made by other demands placed upon them. At the morning conference on the 30th March, it was decided that Nuremberg would be selected as the target for that nights operations. In recent operations Bomber Command had adopted a strategy of not flying direct courses to a target, but using a series of dog leg tracks to try and confuse the German night fighter controllers as to which target they were aiming for. Also diversionary raids were used to add even more confusion and draw away the German night fighters. On this night however it was decided that a direct route from Belgium straight across Germany would be the chosen option. The force would then at a point 50 miles north of NUREMBURG turn south to the aiming point. Meteorological reports indicated a strong tail wind and a cloud layer at cruising altitude would assist the force to reach the target in safety.

The plan was passed to the groups and preparations began at nearly forty airfields down the East coast of England. Almost 800 aircraft were readied, a mixed force of Lancaster's and Halifax's. The crews were briefed for the target and many commented that when the long straight route was revealed a noticeable tension descended on the assembled airmen.

Take off times were set from 19:00 hours, squadrons were allocated a slot in which to depart creating seven waves in the bomber stream. Fifty squadrons provided nearly seven hundred main force aircraft and one hundred Pathfinder aircraft would lead the way and mark the target.

From the start things went wrong. The Metrological forecast was wrong, a Met. Flight had informed Headquarters of a change in the wind speed and direction but this was ignored, also the predicted cloud layer had gone in fact it was a bright clear moonlit night with perfect vision for miles. Another rather strange rarely encountered phenomenon happened, the aircraft were trailing contrails at the cruising altitude, streaming out behind like pointers. Aircrew mentioned that they could clearly see other aircraft all around. The wind was now pushing the force further north and was not pushing from the tail as expected.

The final problem was either pure bad luck or very clever thinking by the German night fighter controllers. They decided to assemble the night fighters over a beacon between Cologne and Koblenze. Two hundred aircraft from all over Germany circled the beacon, and were right under the planned route of the bomber stream. The first three waves of bombers had passed through the area but the the remaining aircraft were easy targets. In the following hour more than eighty aircraft were shot down by the night fighters. Aircrews described watching plane after plane burst into flames and crash or explode in the air. One pilot even told his gunners to stop reporting what they could see as it was much to distressing. Another plane avoided a night fighter and watched as the German pilot just moved across and shot down the aircraft next to them.

Finally the bomber stream reached the turning point and headed south to the aiming point, yet again fate intervened. Thick cloud completely obscured the city and the markers dropped by the Pathfinders disappeared into the cloud and could not be identified. As a result bombs and incendiaries fell over a wide area of countryside and caused little damage to the city. Many aircraft pushed off course by the wind and avoiding the battle en route missed NUREMBURG by many miles. The result was that many bombed SCHWEINFURT by mistake and this did cause damage to several factories.

As the remaining aircraft turned for home they faced a strong head wind and the prospect of running out of fuel as well as nursing damaged planes and avoiding flak. More losses were taken but not as severe as the outward leg Estimates showed 82 aircraft were lost on the outward leg and 13 on the return journey. In the early morning the airfields began to receive their returning planes and it became obvious the scale of the losses. Initial intelligence reports by the crews were discounted as exaggerated and the losses not counted, but the figures started to add up. The final count was set at 95 aircraft lost, 64 Lancaster's and 31 Halifax's plus many more damaged beyond repair. Casualties to aircrew mounted to more than 670 killed or missing.

Three 106 Squadron aircraft were shot down that night with the loss of seventeen crew. Four other crew members survived to become Prisoners of War (POWs), having either been blown out of their aircraft when it exploded or having bailed out over enemy territory.

Nuremberg is located in southern Germany in the federal state of Bavaria and is the second largest city after the state capital Munich. At the time Nuremberg was a centre of communications, industry and an administrative centre for the region and this made it a valid target for Bomber Command from early in the war. Bomber Command had visited Nuremberg on previous occasions starting in August 1940. In December an attack was made on the Nazi party rally grounds, rather symbolic. Air raids continued throughout the following years growing in size as Bomber Command and the USAAF ability to hit back grew. The heaviest raid up until then was on the night of the 10th/ 11th August 1943 when a force of 653 heavy bombers destroyed or damaged over 5000 buildings and killed 585 residents.

At the end of March 1944 Bomber Commands six month winter offensive was coming to an end . Often referred to as the Battle of Berlin it had cost Bomber Command heavily in casualties and lost aircraft but had not achieved its aim in bringing the war to an end by destroying the morale of the German people. Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris had promised that by April the German people would give up the struggle, however they seem to have adopted much the same “Blitz Spirit” as the British population had and carried on.

With the end of the period of long dark nights deep penetration raids into Germany would have to stop. Also with the prospect of the invasion of Europe, Bomber Command would need to change the type of target it selected, indeed the choice would be made by other demands placed upon them. At the morning conference on the 30th March, it was decided that Nuremberg would be selected as the target for that nights operations. In recent operations Bomber Command had adopted a strategy of not flying direct courses to a target, but using a series of dog leg tracks to try and confuse the German night fighter controllers as to which target they were aiming for. Also diversionary raids were used to add even more confusion and draw away the German night fighters. On this night however it was decided that a direct route from Belgium straight across Germany would be the chosen option. The force would then at a point 50 miles north of NUREMBURG turn south to the aiming point. Meteorological reports indicated a strong tail wind and a cloud layer at cruising altitude would assist the force to reach the target in safety.

The plan was passed to the groups and preparations began at nearly forty airfields down the East coast of England. Almost 800 aircraft were readied, a mixed force of Lancaster's and Halifax's. The crews were briefed for the target and many commented that when the long straight route was revealed a noticeable tension descended on the assembled airmen.

Take off times were set from 19:00 hours, squadrons were allocated a slot in which to depart creating seven waves in the bomber stream. Fifty squadrons provided nearly seven hundred main force aircraft and one hundred Pathfinder aircraft would lead the way and mark the target.

From the start things went wrong. The Metrological forecast was wrong, a Met. Flight had informed Headquarters of a change in the wind speed and direction but this was ignored, also the predicted cloud layer had gone in fact it was a bright clear moonlit night with perfect vision for miles. Another rather strange rarely encountered phenomenon happened, the aircraft were trailing contrails at the cruising altitude, streaming out behind like pointers. Aircrew mentioned that they could clearly see other aircraft all around. The wind was now pushing the force further north and was not pushing from the tail as expected.

The final problem was either pure bad luck or very clever thinking by the German night fighter controllers. They decided to assemble the night fighters over a beacon between Cologne and Koblenze. Two hundred aircraft from all over Germany circled the beacon, and were right under the planned route of the bomber stream. The first three waves of bombers had passed through the area but the the remaining aircraft were easy targets. In the following hour more than eighty aircraft were shot down by the night fighters. Aircrews described watching plane after plane burst into flames and crash or explode in the air. One pilot even told his gunners to stop reporting what they could see as it was much to distressing. Another plane avoided a night fighter and watched as the German pilot just moved across and shot down the aircraft next to them.

Finally the bomber stream reached the turning point and headed south to the aiming point, yet again fate intervened. Thick cloud completely obscured the city and the markers dropped by the Pathfinders disappeared into the cloud and could not be identified. As a result bombs and incendiaries fell over a wide area of countryside and caused little damage to the city. Many aircraft pushed off course by the wind and avoiding the battle en route missed NUREMBURG by many miles. The result was that many bombed SCHWEINFURT by mistake and this did cause damage to several factories.

As the remaining aircraft turned for home they faced a strong head wind and the prospect of running out of fuel as well as nursing damaged planes and avoiding flak. More losses were taken but not as severe as the outward leg Estimates showed 82 aircraft were lost on the outward leg and 13 on the return journey. In the early morning the airfields began to receive their returning planes and it became obvious the scale of the losses. Initial intelligence reports by the crews were discounted as exaggerated and the losses not counted, but the figures started to add up. The final count was set at 95 aircraft lost, 64 Lancaster's and 31 Halifax's plus many more damaged beyond repair. Casualties to aircrew mounted to more than 670 killed or missing.

Three 106 Squadron aircraft were shot down that night with the loss of seventeen crew. Four other crew members survived to become Prisoners of War (POWs), having either been blown out of their aircraft when it exploded or having bailed out over enemy territory.

|

The raid was to be the worst night Bomber command would suffer. The 12 per cent loss rate was unsustainable and for the first time more aircraft were lost than were produced. In one night more aircrew were lost than in the whole of the Battle of Britain. And the end result was negligible damage to the intended target.

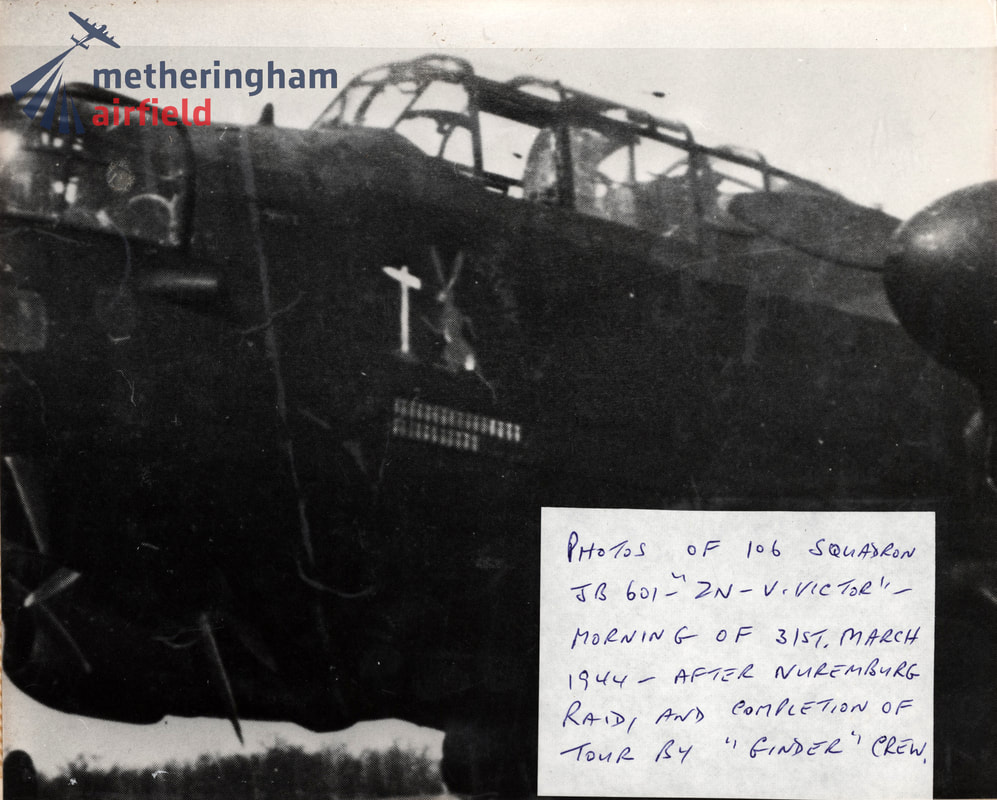

Amidst the terrible collective losses of RAF Bomber Command that night there were many individual tales of bravery and heroism. For some returning crews there might even have been cause for some muted celebration. This photo depicts Lancaster JB 601 ZN-V (Victor) at RAF Metheringham the morning after the raid. For this particular crew, the Nuremburg raid marked the end of their tour. |